The great Roman historian, Livy, provides us with a remarkably vivid picture of early Rome, and leads us to a sound appreciation of the culture that helped the city rise to the splendours of empire. The characters that crowd the pages of Livy’s history are all object lessons on the demands, the duties, and the dynamics of leadership. The story of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus held up to 2000 years of western civilisation the ideal of personal integrity as the essence of great leadership, and the example of Cincinnatus inspired George Washington to resist the temptations of dictatorship or monarchy once his armies had prevailed in the American Revolution. The crisis that brought Cincinnatus to power in Rome was the entrapment of a Roman army led by the consul, Minucius, by the Aequian army. An enemy victory would have opened the way for an attack on Rome itself. But let Livy tell the story.

“The city was thrown into a state of turmoil, and the general alarm was as great as if Rome herself were surrounded. Nautius was sent for, but it was quickly decided that he was not the man to inspire full confidence; the situation evidently called for a dictator, and with no dissentient voice, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was named for the post.

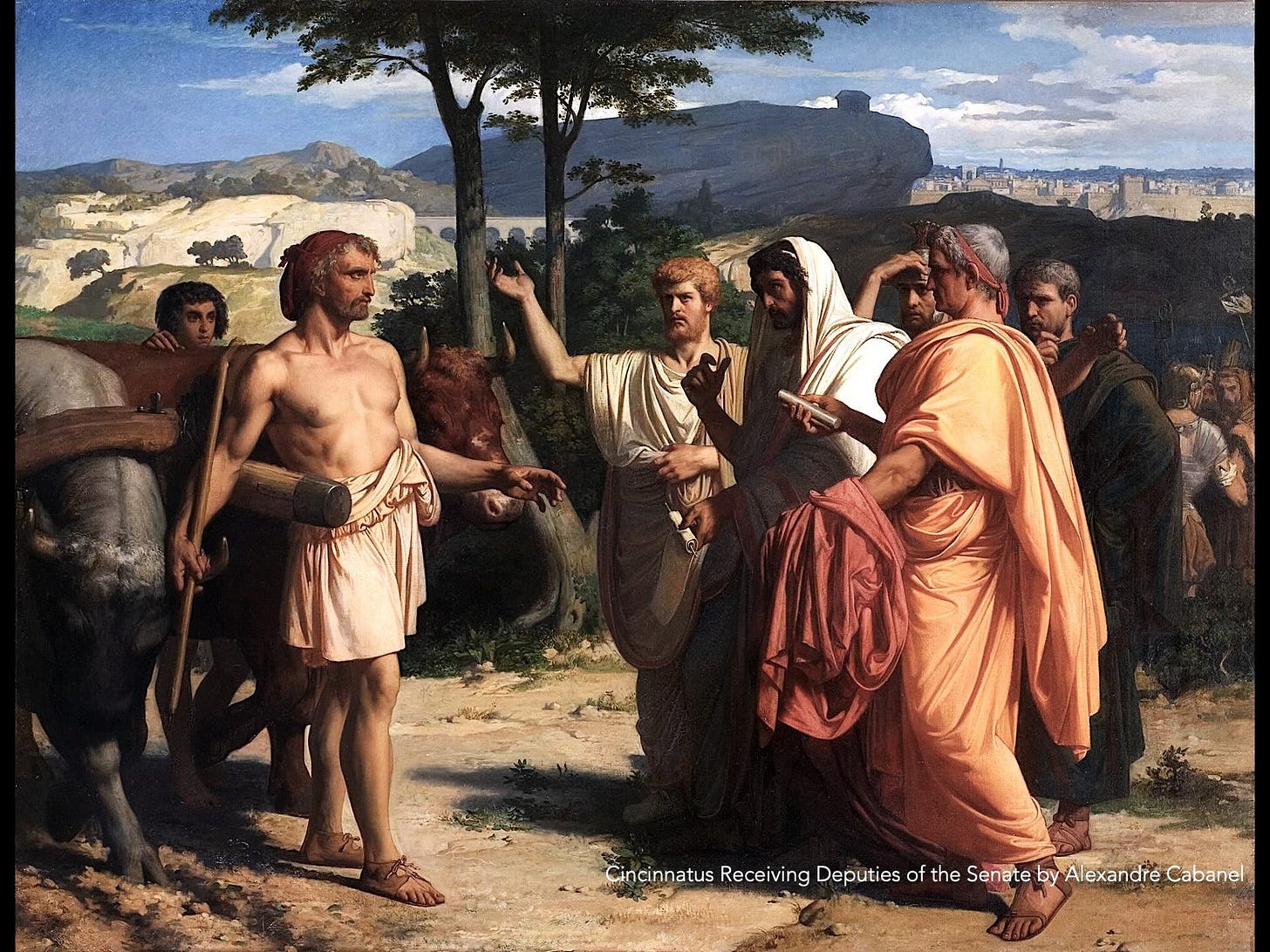

“Now I would solicit the particular attention of those numerous people who imagine that money is everything in this world, and that rank and ability are inseparable from wealth; let them observe that Cincinnatus, the one man in whom Rome reposed all her hope of survival, was at that moment working a little three-acre farm…west of the Tiber, just opposite the spot where the shipyards are today.

“A mission from the city found him at work on his land – digging a ditch, maybe, or ploughing. Greetings were exchanged, and he was asked – with a prayer for God’s blessing on him and his country – to put on his toga and hear the Senate’s instructions. This naturally surprised him, and, asking if all were well, he told his wife Racilia to run to their cottage and fetch his toga. The toga was brought, and wiping the sweat from his hands and face, he put it on.

“At once the envoys from the city saluted him with congratulations, as Dictator; they invited him to enter Rome, and informed him of the terrible danger facing Minucius’ army…the Dictator then appeared before the assembled people to issue his instructions: legal business was to be suspended, all shops closed, and no private business of any kind transacted; all men of military age were to parade before sunset in the Campus Martius with their equipment, each man bringing with him a five-days’ bread ration and twelve stakes…

“The Dictator’s orders were promptly executed…Then the column of march was formed, all prepared, should the need arise, for instant action, and moved off with Cincinnatus at the head of the infantry and Tarquitius in command of the mounted troops…

“In each division, infantry and cavalry, could be heard such words of command or encouragement as the occasion demanded; the men were urged to step out, reminded of the need for haste, in order to reach the scene of action that night, pressed to remember that a Roman army with its commander had already been three days under siege…

“At midnight the army reached Algidus and halted not far from the enemy’s position. The Dictator rode around it on his horse, to inform himself, so far as he could in the darkness, of the extent and layout of their camp…

“It was still dark when the fight began, and the relieving troops of Cincinnatus knew by the war-cry of their beleaguered friends that they, too, were in action at last…Caught as it were between the two fires, the Aequians soon gave up the struggle and begged both Cincinnatus and Minucius not to proceed to a general massacre but to disarm them and let them go with their lives. Minucius referred them to the Dictator, who accepted their surrender, but on humiliating terms…

“In Rome the Senate was convened by Quinctius Fabius, the City Prefect, and a decree was passed inviting Cincinnatus to enter in triumph with his troops. The chariot he rode in was preceded by the enemy commanders and the military standards, and followed by his army loaded with its spoils…

“Only the impending trial of Volscius for perjury prevented Cincinnatus from resigning immediately. The tribunes, who were thoroughly in awe of him, made no attempt to interfere with the proceedings, and Volscius was found guilty and went into exile…Cincinnatus finally resigned after holding office for fifteen days, having originally accepted it for a period of six months.”

Excellent thanks!